Basic HTML Version

12

Rich Pressure, Poor Ecosystems

- by Edgar Hertwich

RESEARCH

I just returned from my weekly trip to the

supermarket: in addition to Kenyan roses,

Brazilian melons, Israeli oranges, Dutch

tomatoes, kiwis from New Zealand, and

potatoes from Saudi Arabia (!), I have, for

the first time, found minced beef from

Botswana, sold for just over half the price

of the Norwegian one. We have over the

years become accustomed to the increas-

ing variety and prettiness of food we find

on supermarket shelves, regardless of the

season. Meanwhile, we are generally ob-

livious to the ecological cost of this bounty.

New scientific research now shows that,

indeed, consumers in some rich countries

live well above their ecological means and

in the process threaten global biodiversity

(see also previous post). They can do so only

because of international trade.

The increasing intensity and extent of hu-

man land use is a major threat to ecosys-

tems. Estimates by the Gobal Footprint

Network show that humanity already uses

two thirds of the fertile land available on

this planet; calculations by the Institute of

Social Ecology in Vienna demonstrate that

humans in fact appropriate a full quarter of

terrestrial biomass. According to the Millen-

nium Ecosystem Assessment, habitat loss

– mostly through land use – is the number

reason for the extinction of species on the

planet. Climate change, hunting and fish-

ing, the release of nitrogen and phosphorus

– in large part due to fertilizers used in ag-

riculture, and alien species also contribute

significantly to the largest mass extinction

event since the disappearance of the dino-

saurs.

In the most encompassing and detailed

study of the processing, trade and con-

sumption of products of land use, we

quantify the land footprint of 87 individual

countries and 26 more aggregate regions,

covering the entire global economy. We ex-

press land use in terms of hectares of global

average crop land productivity, the meas-

ure of the well-established Ecological Foot-

print. Our analysis shows that the land foot-

print for different countries can be largely

explained by only two factors: wealth and

the availability of fertile land. Richer coun-

tries have a higher footprint: the per capita

footprint of Germany and France in 2004

was 2.7 global hectares per person, China’s

0.8 and India’s only 0.6 gha/p. At the same

time, countries with a lot of land available

use more of it; Canada’s land footprint at

3.9 gha/p was much large than Japan’s (2.0

gha/p); Brazil used 2.3 gha/p, while Bulgaria

with the same GDP per person used only 1.7

gha/p. (If you want to know your country’s

footprint, see our visualization.) Through-

out our dataset, a doubling of per capita in-

come increases the footprint by 35%; while

a doubling of domestic land availability in-

creases the footprint by 23%.

You are forgiven to think that, well, overall,

this is not so surprising. The study, in the

meantime, resolves a scientific mystery. If

you measure biomass use in different coun-

tries, as the aforementioned Institute of

Social Ecology has done, it varies a lot but

does not depend much on wealth. If you

look historically at biomass use per capita,

it has gone down instead of up (see meta-

bolic rate). This trend is contrary to the ob-

servation for food consumption, which in-

creases with increasing wealth; just witness

the present obesity epidemic. The explana-

tion, in our eyes, lies in the displaced land

use which was not fully considered in the

work of the colleagues from the Institute

for Social Ecology. Displaced land use, in

fact, increases proportional to income per

capita and does not depend at all on the

domestic availability of land. The replace-

ment of draught animals and fire wood by

fossil fuels probably also plays a role for the

historical development.

Paradoxically, the beef from Botswana I

found in the supermarket today is a success

for Friends of the Earth and other green

and development groups who have long

lobbied for a greater access of develop-

ing countries’ agricultural products to the

markets of the rich world. We have not in-

vestigated whether the ecological impact

of beef production in Botswana is higher

or lower than in Norway. Looking just at a

package of minced meat, it may be a good

thing, not least because it provides in-

come to a relatively poor population. The

problem is that international trade moves

the ecological impact out of our sight.

Ecological limits disappear. Our results show

that Japan and South Korea displace twice

as much land use as they have fertile land

available domestically. Also in Europe, we

live above our biocapacity: Germany’s land

footprint is 30% higher than the amount of

fertile land available, the land footprint of

the Netherlands and Belgium is two and a

half times their biocapacity.

Our study indicates that as emerging

economies get richer and the population

grows further, nature will be squeezed. By

2050, basically all available fertile land will

be used to satisfy increased consumption

levels of a larger population. Some relief for

nature may come from an intensification of

land use and an increase of fertile land area

through irrigation. At the same time, cli-

mate change, erosion, salinization of soils as

a result of irrigation, and urbanization will

reduce the available fertile land. Reduced

biodiversity will make us more vulnerable

to pests. Given the systematic net displace-

ment from rich to poor countries, we can

expect that biodiversity will be especially

threatened in those remaining poor coun-

tries which have underdeveloped institu-

tions and hence no capacity to protect bio-

diversity.

None of this is inevitable; we can reduce

our land footprints by reducing the over-

consumption and waste of calories, limiting

the consumption of animal products which

already cause 28% of global land use, pre-

serve forests and avoid sealing too many

surfaces. Avoiding a further squeeze of

poor countries’ ecosystems requires chang-

ing the current global land use pattern that

has been identified in our research. Displac-

ing land use to poor countries makes us co-

responsible for protecting their biodiversi-

ty, and mechanisms need to be developed

for doing so.

Contact person: Professor Edgar Hertwich,

edgar.hertwich@ntnu.no

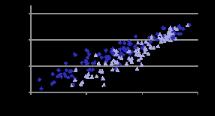

Figure: Land use embodied in imports of different countries as a function of the countries’ income per

capita. Each symbol is a country, and each country appears twice; dark diamonds reflecting nominal

GDP, triangles for purchasing power parity corrected GDP. (carbonfootprintofnations.com)