Etikk i praksis. Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics (2016), 10 (1), 5–13

Algorithmic regulation and the global default: Shifting norms in Internet technology

Ben WagnerCentre for Internet & Human Rights, European University Viadrina, bwagner@europa-uni.de

The world we inhabit is surrounded by ‘coded objects’, from credit cards to airplanes to telephones (Kitchin & Dodge, 2011). Sadly, the governance mechanisms of many of these technologies are only poorly understood, leading to the common premise that such technologies are ‘neutral’ (Brey, 2005; Winner, 1980), thereby obscuring normative and power-related consequences of their design (Bauman et al., 2014; Denardis, 2012). In order to unpack supposedly neutral technologies, the following paper will look at one key question around the technologies used on the global Internet: how are the algorithms embedded in software governed? The paper will look in detail at the question of algorithmic governance before turning to one specific example: content regulatory regimes. Finally, it will focus on drawing conclusions in understanding the normative frameworks embedded in technological systems.

Keywords: algorithms, governance, freedom of expression, technology & society, ethics of technology

Governing algorithms

The attempts by public regulators to influence the mathematical algorithms present within automated software programs constitute one particularly interesting Internet governance practice. The 2015 scandal around the software algorithms used to manipulate emissions in Volkswagen cars is one obvious example of the challenges related to their governance (Burki, 2015; Schiermeier, 2015). This is particularly clear in this case, as the regulators of these cars did not even have access to the actual software embedded in the cars.

In the context of this article, algorithms represent a large part of the decision-making processes that are termed here ‘first-order rules.’ These are automated decision-making processes, governed by algorithms of varying degrees of complexity. They are also the foundation of many rules and regulations related to information control. In its simplest form, a Facebook algorithm filters large amounts of content, such as user posts, to try and decide whether the content is permissible. The algorithm may, for example, be set to filter out flesh-coloured images, those that contain swear words or those that come from a certain part of the world and repeatedly ask for a bank account. However, the algorithm can also be set to learn from human decisions, replicating their decision-making processes, operational practices, stereotypes, habits and prejudices (Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2007). For example, “computational hiring systems have found that low commute time corresponds to low turnover” (Zeynep Tufekci, York, Wagner, & Kaltheuner, 2015), which in turn correlates strongly with both class and race. It has also been suggested that in “the case of extremist or terrorist content the recommender system can keep ‘recommending’ further extremist material once a user has watched just one” (Zeynep Tufekci et al., 2015), helping to strengthen the creation of “ideological bubbles” (O’Callaghan, Greene, Conway, Carthy, & Cunningham, 2014).

Of course, machine learning typically uses a large sampling of individuals, in the hope that individual biases wash out over time. However, in these dimensions a level of complexity sets in which becomes difficult to manage. The reason is that these automated systems have moved beyond simple variable-based responses, and are instead responding to their surrounding based on a ‘machine learning’ process. As it is often too costly to stop this learning process, case-by-case filters are occasionally introduced in order to modify the prima facie responses of the system.

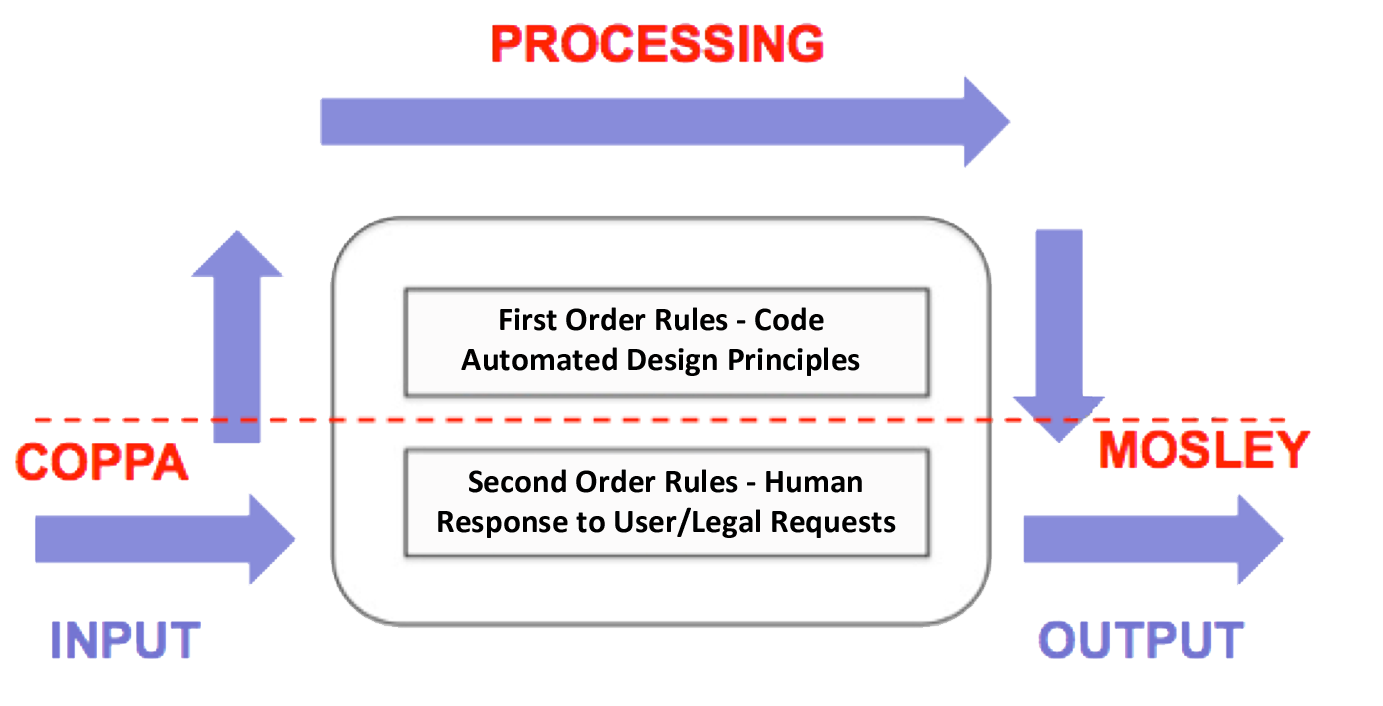

Figure 1: First- and second-order

regulatory rules

Thus, a distinction needs to be made between first-order rules, which are automated in computer code, and second-order rules, which involve individual changes to the output created by these algorithms. A second-order rule would remove some of the outputs of the algorithm that are unwanted, for example limiting individual Google search results by filtering out certain images or keywords. A typical example here is the Max Mosley case, where a judge required Google to remove certain specific outputs from its search engine results (Stanley, 2011). The algorithm itself did not, however, need to be changed, rather its results simply needed to be limited.

Figure 2: First- and second-order rules in practice

Similar things can be said about the COPPA regulatory framework, which attempts to protect minors from advertising and thus limits the data that private companies can legally collect from individuals (Wagner, 2013). Both the Max Mosley court decision and COPPA limit the algorithmic decision-making input and output, but not the processing of data conducted by the algorithm itself. In the manner used above, COPPA and Mosley are both second-order rules in that they limit data inputs or outputs of an algorithm without actually changing the algorithm itself.

Actually tweaking the variables of the data processing algorithm and changing the way the machine learns are tasks reserved for a select few engineers, who optimise and experiment on the algorithms that Google or Facebook use globally. Although public regulators have not yet been able to influence Google algorithms, the FTC and EU investigation into ‘Search neutrality’ revolves precisely around this question (Manne & Wright, 2012; Petit, 2012; van Hoboken, 2012). Can an Internet search monopoly be compelled to change not only its second-order principles, but its first-order principles as well? Can regulators require Google to force its algorithm to act in certain ways towards certain competing sites? This would in effect require the public regulators to have access to the algorithm, employ individuals capable of understanding its properties and be able to modify it effectively in the interests of the public. While it is not entirely clear what the public interest is in this context, parliaments, courts, private companies and public authorities are vying to define it (Bennett, 2010; EDPS, 2016; Schulz, 2016; Stanley, 2011).

One area where algorithmic regulation has already begun to be discussed is the area of financial regulation. Due to the increasing use of automated high-speed trading systems and their potentially destabilising effect on financial markets, regulators have begun to demand both transparency over high-speed trading algorithms and the ability to modify these algorithms if they are considered unstable (Steinbrück, 2012). A policy paper written by Peer Steinbrück, the social democratic (SPD) candidate for German chancellor in 2013, recommends the following procedures to deal with high-speed financial trading systems:

The core of an effective regulation needs to be a public certification system not just for trading companies, but for the trading algorithms themselves. This certification system will first analyse the algorithm based on its trading strategy: dangerous trading strategies must be banned! Moreover the algorithms will have to undergo a stress test to ascertain their stability (Steinbrück, 2012, translation by the author).This shift away from regulating the human beings that are responsible for developing the algorithmic trading system and towards the algorithms themselves is a particularly interesting development. It assumes that it is possible to objectively predict the responses of certain algorithms to different types of situations and that the assessment of such algorithms is more effective than the assessment of the people developing it. This reflects a shift similar to the one noted above of increasingly specific governance practices. Faced with an increasing level of complexity and their own regulators’ lack of leverage, public actors are responding with ever more precise and finely tuned governance practices to get to the heart of the systems they are trying to gain control over.

The high level of precision in governance that is possible in turn gives the regulator a great deal of leverage with only relatively small changes to the regulatory mechanism, plus all of the advantages of using software code which lie in its automation and scalability, i.e. that the cost of repetition is low or negligible and in most cases can quickly be used not just for a small number but can also be quickly and easily replicated up to a large number of repetitions.

For certain types of economic and even socio-political regulation, this form of algorithmic regulation may be quite effective, insofar as it modifies existing market practices which are themselves already based on algorithms. However, such regulation relies on oligopolistic or monopolistic markets and is extremely invasive for the companies being regulated, which are being asked to modify what can be considered the core of their business. It is also likely very difficult for all but the largest countries to compel companies to modify the first-order rules which govern their algorithms.

Content regulatory regimes

On 29 June 2015 the Counter Extremism Project (CEP) opened its offices in Brussels. A highly influential and swiftly expanding group, it called for “[s]ocial media companies that don't remove extremist material from their websites [to] face sanctions” (Stupp, 2015). This organisation includes many of the hallmarks of how content on the global Internet is governed: a government-funded non-profit with the ability to exert considerable pressure on private sector actors through expertise in a specific subject area. The following section will attempt to explain how such organisations come about and result in the emergence of a “regime of competence” (Wenger, 2009). It will be argued that communities of practice construct a global “regime of competence” (Wenger, 2009) which enables them to govern in these areas. This regime of competence has certain attributes and actor constellations that will be discussed in order to understand how the overall regime is governed.

This leads to what is being discussed here as the global default. The ‘global default’ is a global regime of competence that defines permissible online content. While parts of the regime draw from public regulation and even state legislation, the vast majority of the regime is based on private norms and practices. The regime itself is embedded within agreements between private sector actors who are responsible for definition, management and implementation of the regime. Insofar as the public sector participates in this system, the institutions have adapted to fit this model, relying primarily on private sector notice and takedown procedures for enforcement. While all of this of course takes place under the shadow of state hierarchy (Héritier & Eckert, 2008), the extent of public sector coercion is typically relatively limited.

In order to make these regimes performative, many of the private sector actors embed their norms in technology. Thus, users of online search engines are likely aware of the many different lists used to filter content out of their searches. One such list is provided by the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) and automatically implemented by most large online search engines. This leads the small German quasi-public NGO Jugendschutz.Net to set the global standard on pictures of children in provocative sexual poses (‘Posendarstellungen’), the U.S. corporation Facebook to set the global standard for speech regulation in regard to nudity in social spaces online and the British private sector initiative, the IWF, to provide the foundational definition of child sexual abuse material, which is blocked not just in the UK, but by online service providers across the world.

Similar things can be said for the role of the U.S. CDA Supreme Court decision or the role of waves of UK governmental coercion on IWF policy (Goldsmith & Wu, 2006; Nussbaum, 2011), both of which heavily impacted the global default of speech. Strangely, however, perhaps the most important piece of legislation influencing speech online is COPPA (Wagner, 2013), which defines the age at which corporations can advertise to human beings. Indeed, much of the relevance of these public sector actors depends on the predominance of private companies. The influence of COPPA in the U.S., as well as the influence of the British government, would be far less if large quasi-monopolies like Google or Facebook did not exist. What has been called “U.S. Free Speech Imperialism” (Rosen, 2013) not only has effects beyond the U.S., but is also influenced by actors outside the U.S. At the same time, the nature of the global default of speech is not solely influenced by factors promoting speech – such as the U.S. First Amendment.

Notably, this form of market dominance exists in other global regulatory regimes as well. In regard to the governance of global supply chains, for example, the “power of such ‘parameter-setting’ firms, such as Shimano in bicycles and Applied Materials in semiconductors, is not exerted through explicit coordination, but through their market dominance in key components and technologies” (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005, p. 98). As with large Internet companies, market dominance translates into an informal private governance regime of the respective area, enabling the creation of a private regulatory regime.

In the area of financial service regulation, Cafaggi (2011) argues that while some of the regulation in the financial services area is industry driven, such as the “International Accounting Standards Board (IASB),” (Cafaggi, 2011, p. 36) there are also examples such as the “International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA)” (Cafaggi, 2011, p. 36), which follow a multi-stakeholder model of governance, although other competing forms of governance also exist. Interestingly, the nature of the ISDA’s governance is disputed within academia, with other authors beyond Cafaggi referring to ISDA simply as “the largest global financial trade association” (Biggins & Scott, 2012, p. 324), whose “lobbying influence cannot be downplayed” (Biggins & Scott, 2012, p. 323).

Thus it seems reasonable to suggest that there are similar elements of governance in other domains than Internet governance. On the one hand, elements of the ‘global default’ and its private governance regime share some similarities with global supply chains, where informal private regulatory regimes are created through market dominance. On the other hand, there are some similarities to global financial regulation, where the nature of multi-stakeholder governance is contested.

Social norms embedded in technology

What should be evident from the discussion above is that the norms embedded in technology are not transparent to the vast majority of their users. These norms are also not static, rather they are objects of persistent and on-going struggles (Denardis, 2012). This is particularly the case regarding connected digital technologies that can be and are being constantly changed, updated and modified. This malleability makes them particularly attractive for numerous actors who wish to govern through them.

Importantly, while the social norms embedded in technology are evidently influenced by legal regimes, they are not the same as the relevant legal regimes and often diverge from them in numerous ways. As discussed, Facebook’s rules on Free expression have little to do with the First Amendment of the United States Constitution or indeed the legal framework for freedom of expression of any country in the world. Likewise, algorithms used in the global search engine market evidently pose considerable challenges to competition law and are thus currently under investigation (Kovacevich, 2009; Pollock, 2009).

However, the danger in looking at the normative frameworks embedded in technology simply as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ algorithms, is that they are neither. Rather they are products of a socio-technical process that can only be understood by looking both at technology and human interaction with it (Brey, 2005). Algorithms, like any other technology, can thus be considered “biased but ambivalent” (McCarthy, 2011, p. 90).

What can strongly be suggested, however, is that technologies are key loci of control where power is distributed and redistributed (Klang, 2006; Z Tufekci, 2015). Thus, understanding which norms are embedded in technology also assists in understanding the power structures that govern the production and usage of technology. Although this process of socio-technical construction remains relatively opaque to the general public, it is becoming increasingly influential in a variety of systems within society.

In this context, it is necessary to return to the distinction between first- and second-order rules. The reason this distinction is so important is that while second-order rules are overwhelmingly non-automatable and require repeated input for each individual case, first-order rules are necessarily automatable as they are part of automated technical processes. These are particularly attractive to governance regulators and companies alike as a form of regulation since they scale, an important criterion for effective governance of any digital technology. Without scalability, regulators are left to constantly repeat the same individual case-by-case challenges of systems, rather than being able to influence the system as a whole.

Figure 1: First- and second-order

regulatory rules

Indeed, in many cases the governing bodies involved do not even have access to key algorithms, as the 2015 scandal around Volkswagen’s manipulation of emissions standards within its motors suggests. By simply refusing or failing to provide key software to relevant automobile regulators around the world, Volkswagen was able to sell cars that did not meet relevant government emissions standards. This example clearly demonstrates the power embedded in algorithms and the attractiveness of a scalable governance mechanism. It also clearly suggests that not only is technology not neutral, it represents a multi-layered battleground of existing struggles around social norms (Tawil-Souri, 2015). Thus, technological infrastructure itself reflects many of the key power struggles of the past decades, whether these are related to the future of the environment and emissions rates of cars, the appropriate regulation of the stock market and financial trading or the control of Internet content. In all of these cases, technology is neither neutral nor good or evil, but simply reflects existing power structures and struggles that through malleable technology directly impact the life-world of human beings.

References

Bauman, Z., Bigo, D., Esteves, P., Guild, E., Jabri, V., Lyon, D., & Walker, R. B. J. (2014). After Snowden: Rethinking the Impact of Surveillance. International Political Sociology, 8(2), 121–144. CrossRef

Bennett,

B. (2010).

YouTube is

letting users

decide on

terrorism-related

videos. Los

Angeles Times.

Retrieved

February 11,

2012, from http://articles.latimes.com/2010/dec/12/nation/la-na-youtube-terror-20101213

Biggins, J., & Scott, C. (2012). Public-Private Relations in a Transnational Private Regulatory Regime: ISDA, the State and OTC Derivatives Market Reform. European Business Organization Law Review, 13(03), 309–346. CrossRef

Brey,

P. (2005).

Artifacts as

social agents.

In H. Harbers

(Ed.), Inside

the politics

of technology:

Agency and

normativity in

the

co-production

of technology

and society

(pp. 61–84).

Amsterdam

University

Press.

Burki,

T. (2015).

Diesel cars

and health:

the Volkswagen

emissions

scandal. The

Lancet.

Respiratory

Medicine,

3(11),

838-839. CrossRef

Cafaggi, F. (2011). New Foundations of Transnational Private Regulation. Journal of Law and Society, 38(1), 20–49. CrossRef

Denardis,

L. (2012).

Hidden Levers

of Internet

Control. Information,

Communication

& Society,

15(5), 37–41.

CrossRef

EDPS.

(2016). EDPS

starts work on

a New Digital

Ethics.

Brussels,

Belgium.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. CrossRef

Goldsmith,

J. L., &

Wu, T. (2006).

Who

controls the

Internet?

illusions of a

borderless

world.

Oxford

University

Press.

Héritier,

A., &

Eckert, S.

(2008). New

Modes of

Governance in

the Shadow of

Hierarchy:

Self-regulation

by Industry in

Europe. Journal

of Public

Policy,

28(01),

89-111. CrossRef

Kanter, J. and Streitfeld, D. (2012, May 21). Europe weighs Antitrust Case against Google, urging search changes. The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/22/business/global/europe-warns-google-over-antitrust.html?_r=0

Kitchin,

R., &

Dodge, M.

(2011).

Code/space

software and

everyday life.

MIT Press.

Klang,

M. (2006). Disruptive

technology:

effects of

technology

regulation on

democracy.

Göteborg:

Department of

Applied

Information

Technology,

Göteborg

University.

Kovacevich,

A. (2009).

Google Public

Policy Blog:

Google’s

approach to

competition. Google

Public Policy

Blog.

Retrieved

October 27,

2012, from http://googlepublicpolicy.blogspot.de/2009/05/googles-approach-to-competition.html

Manne,

G., &

Wright, J.

(2012). If

Search

Neutrality is

the Answer,

What’s the

Question.

Colum. Bus.

L. Rev.

151.

McCarthy,

D. R. (2011,

January). Open

Networks and

the Open Door:

American

Foreign Policy

and the

Narration of

the Internet.

Foreign

Policy

Analysis,

7(1) CrossRef

Nussbaum,

M. C. (2011).

Objectification

and Internet

Misogyny. In

S. Levmore

& M. C.

Nussbaum

(Eds.), The

Offensive

Internet:

Privacy,

Speech, and

Reputation.

Harvard

University

Press.

O’Callaghan,

D., Greene,

D., Conway,

M., Carthy,

J., &

Cunningham, P.

(2014). Down

the (White)

Rabbit Hole:

The Extreme

Right and

Online

Recommender

Systems. Social

Science

Computer

Review,

33(4),

459–478. CrossRef

Pariser,

E. (2011).

The filter

bubble : what

the Internet

is hiding from

you. New

York: Penguin

Press.

Pollock,

R. (2009). Is

Google the

next

Microsoft?:

competition,

welfare and

regulation in

internet

search.

Cambridge:

University of

Cambridge

Faculty of

Economics.

Rosen,

J. (2013). Free

Speech on the

Internet:

Silicon Valley

is Making the

Rules. New

Republic.

Retrieved May

9, 2013, from

http://www.newrepublic.com/article/113045/free-speech-internet-silicon-valley-making-rules#

Schiermeier,

Q. (2015). The

science behind

the Volkswagen

emissions

scandal.

Nature News. CrossRef

Schulz,

M. (2016). Keynote

speech at

#CPDP2016 on

Technological,

Totalitarianism,

Politics and

Democracy.

European

Parliament.

Retrieved

February 12,

2016, from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/the-president/en/press/press_release_speeches/speeches/speeches-2016/speeches-2016-january/html/keynote-speech-at--cpdp2016-on-technological--totalitarianism--politics-and-democracy

Stanley,

J. (2011). Max

Mosley and the

English Right

to Privacy.

Wash. U. Global

Stud. L. Rev.,

10(3), 641. http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol10/iss3/7

Steinbrück,

P. (2012).

Vertrauen

zurückgewinnen:

Ein neuer

Anlauf zur

Bändigung der

Finanzmärkte.

Berlin,

Germany.

Stupp,

C. (2015). Social

media

watchdog:

Twitter is the

gateway drug

for

extremists.

EurActiv.

Retrieved July

28, 2015, from

http://www.euractiv.com/section/justice-home-affairs/news/social-media-watchdog-twitter-is-the-gateway-drug-for-extremists/

Sunstein,

C. (2007). Republic.com

2.0.

Princeton:

Princeton

University

Press.

Tawil-Souri,

H. (2015).

Cellular

Borders:

Dis/Connecting

Phone Calls in

Israel-Palestine.

In L. Parks

& N.

Starosielski

(Eds.), Signal

Traffic:

Critical

Studies of

Media

Infrastructures

(pp. 157–182).

Tufekci,

Z. (2015).

Algorithms in

our Midst:

Information,

Power and

Choice when

Software is

Everywhere.

Proceedings of

the 18th ACM

Conference on

Computer

(p. 1918). CrossRef

Tufekci,

Z., York, J.

C., Wagner,

B., &

Kaltheuner, F.

(2015). The

Ethics of

Algorithms:

from radical

content to

self-driving

cars.

Berlin,

Germany.

van

Hoboken, J. V.

J. (2012).

Search Engine

Freedom: On

the

implications

of the right

to freedom of

expression for

the legal

governance of

Web search

engines.

University of

Amsterdam

(UvA). http://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.392066

Wagner,

B. (2013).

Governing

Internet

Expression:

how public and

private

regulation

shape

expression

governance. Journal

of Information

Technology

& Politics,

10(3),

389-403. CrossRef

Wenger,

E. (2010).

Communities of

practice and

social

learning

systems: the

career of a

concept. In

Blackmore, C.

(ed.), Social

learning

systems and

communities of

practice

(pp. 179-198).

Springer

London. CrossRef

Winner,

L. (1980). Do

Artifacts Have

Politics? Daedalus,

109(1),

121–136.

Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024652