By Jeroen Salman

As an off spin of the Dutch Generality (State) Lottery, founded in 1726, all kinds of lottery games flooded the market. The excitement of the lottery fantasy was now transferred to a domestic setting as well. The paper games that have stood the test of time contain intriguing material. They were often richly illustrated and thus offer a visual representation of contemporary lottery culture. Moreover, they contain textual material such as captions, mottos and instructions, that contextualise the impact of lotteries on society. To illustrate the wealth of these sources, I will discuss two early examples of these lottery games.

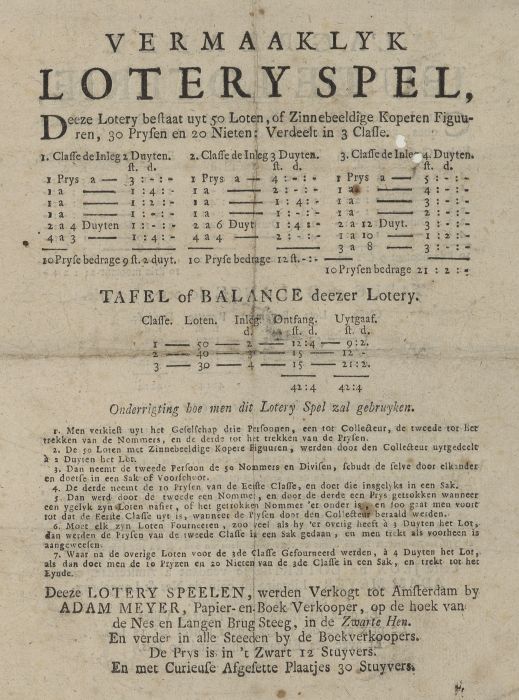

The Amsterdam bookseller Adam Meyer was probably the first who published a Vermaaklyk Lotery Spel [Entertaining Lottery Game] around 1755.[1] The game is remarkably similar to the official state lottery, which had the form of a so-called class lottery. These class lotteries worked with a predetermined number of tickets and prizes and were divided into series or classes. The classes were drawn with some time in between. The size of the prizes increased with the classes, as did the price of the lottery tickets. If your ticket has no prize in the previous class, you have the chance to continue playing, by exchanging the ticket for a more expensive one. People could also buy a lottery ticket for all classes at once. In this case the tickets were slightly cheaper. When you win in the penultimate class, part of the costs were refunded.[2]

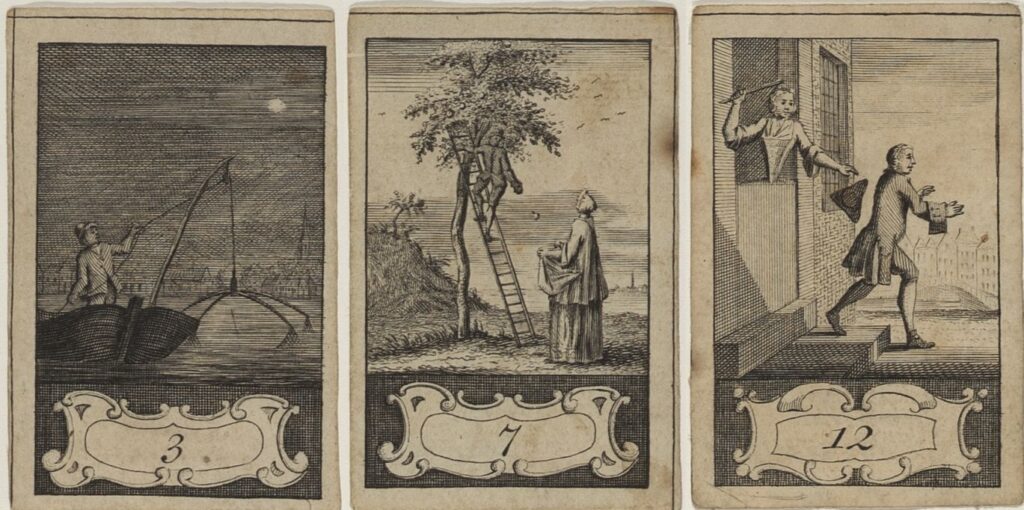

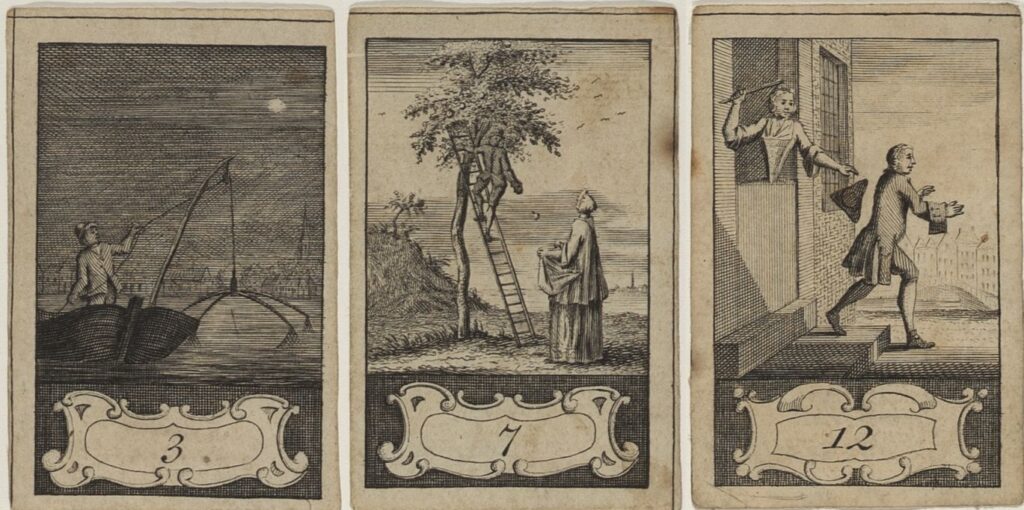

Meyer’s lottery game had three different classes. It further comprised fifty engraved lottery tickets with emblematic images, an equal number of tickets with lottery verses or mottos (‘deviesen’) and tickets with prizes or without prizes. The nicely illustrated tickets were engraved by Caspar Philips Jacobsz (1732-1789), known in these days as a skilled etcher, draftsperson and engraver. A separate broadsheet contained the instructions and rules.

Uncoloured this whole set would cost 12 stivers, and (hand)coloured one had to pay 30 stivers. According to the instructions three ‘officials’ were assigned the role of collector, the person who drew the tickets and the person who drew the prizes. The collector ‘sold’ the tickets for two dimes to the players and also handed out the prizes. The procedure was repeated for every separate class.[3]

The images do not depict the event of the lottery itself, but use the metaphor of game playing as a symbol for the fortunes and perils of life and love in general. The images are accompanied by short moralistic or entertaining inscriptions and mottos. Ticket 3 for instance, shows a fisherman and contains a motto that refers to the uncertainties and hardship of his work: ‘Waited in vain, day and night’. On ticket 7 we see a man standing on a ladder and picking an apple high up in the tree. The motto reads: ‘he who dares wins’. Ticket 12 is mildly satirical about money, marriage and livelihood. A man is kicked out of his house by his wife, because all the money (‘spent on the lottery?’) is gone.

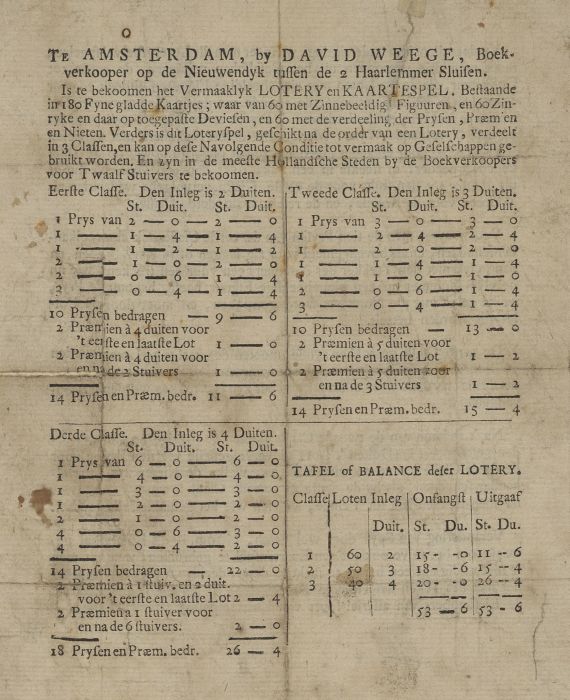

The Amsterdam bookseller David Weege, active between 1748-1787, produced around the same period an undated Vermaaklyk loterye en kaarte Spel [Entertaining lottery and card game]. As the title indicates this lottery game is multifunctional.[4] It consists of 60 engraved lottery tickets with a wide variety of scenes, but 52 of them have trump symbols (hearts, diamonds, clubs and spades) and together form a complete deck of cards.

The images of these playing cards represent, more directly than the Meyer game, the aspirations, dreams and fortunes of the lottery fantasy. [5] Ticket 6, for instance, shows a happy man standing beside a table filled with coins. The accompanying motto states: ‘money is a delight for the eyes’. In some cases playing the lottery is connected to the risks of colonial adventures. Ticket 8 shows a man with a lottery ticket in one hand and a sign that reads ‘for the last time’ in his other. In the back Batavia is depicted, the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company. Is this also the last time that he invests in these oversea trades?

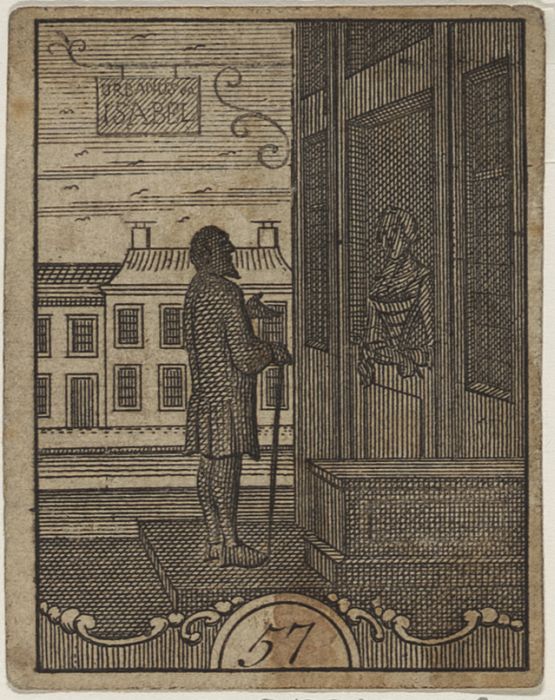

The eight tickets that are not part of the card game tell their own stories and several of them represent the perils of marriage and love life. Especially ticket 57 is a telling example. It depicts a man standing in front of a house and a woman standing in the doorway. The house has a signboard with the inscription ’Urbanus en Isabel’. These names refer to a popular narrative about the couple Urbanus and Isabel who get divorced very soon after their marriage was concluded. Urbanus not only leaves the house, but also steals the money and jewels of his wife and leads a dissolute life with alcohol and prostitutes. After a while, however, he returns to his wife penniless and begs her to be allowed in. Isabel has her hesitations, but eventually accepts his apologies. After the reunion they even get married again.[6] The motto accompanying this ticket states that lottery tickets as well as marriage stories are present always and everywhere.

[1] Vermaaklyk Lotery Spel, Amsterdam: Adam Meyer, [1755]. Atlas van Stolk collection, no. 3971. See P.J. Buijnsters and Leontine Buijnsters-Smets, Papertoys. Speelprenten en papieren speelgoed in Nederland (1640-1920). Zwolle: Waanders, 2005, pp. 26-28, 121.

[2] G.A. Fokker, Geschiedenis der loterijen in de Nederlanden. Eene bijdrage tot de kennis van de zeden en gewoonten der Nederlanders in de XVe, XVIe, en XVIIe eeuwen. Amsterdam: Frederik Muller, 1862, p. 129.

[3] Buijnsters and Buijnsters-Smets, Papertoys, pp. 26-28.

[4] Atlas van Stolk collection, no 3969.

[5] See about similar emblematic card games: Jeroen Salman, ‘Playing Games with the Financial Crisis of 1720. The April Card in Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid, In W. N Goezmann, C. Labio, K. G Rouwenhorst, & T. G Young (Eds.), The Great Mirror of Folly. Finance, culture, and the crash of 1720. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, pp. 235-247.

[6] See more about this story and penny prints in general, Juan Gomis and Jeroen Salman, ‘Tall Tales for a Mass Audience. Dutch Penny Prints and Spanish Aleluyas in Comparative Perspective’, Quaerendo 51 (2021) p. 95–122, especially p. 106.

Jeroen Salman

Jeroen Salman is Associate Professor at Universiteit Utrecht, and is a cultural historian who specialises in early-modern book history and the history of science. He is a reputed expert on European popular print culture with a large international network. He was the leader of the project ‘The European Dimensions of Popular Print Culture’ (EDPOP, 2016-2018) that aimed to develop an international network and a virtual research environment to facilitate and stimulate innovative research on European popular print culture.