By Inga Henriette Undheim

When playing the lottery, why do some of us insist on gambling on self-composed series of ‘lucky numbers’ even though we know that lottery drawings are determined solely by chance?

In this post, we shall have a look at a selection of fictional texts in an attempt to find some answers. But first, let’s head back to the early 1770s, when the Genoese-style number lottery (“the lotto”) was established in the Nordic countries, and the first attempts to explain its principles were printed and distributed.

The Genoese lottery was established in Denmark-Norway, as well as in Sweden, in the early 1770s – more specifically in 1771. In Denmark-Norway, this event coincided with another historical event, namely three exceptional years of press freedom in the short, but significant reign of Johan Friedrich Struensee (1770–1773).

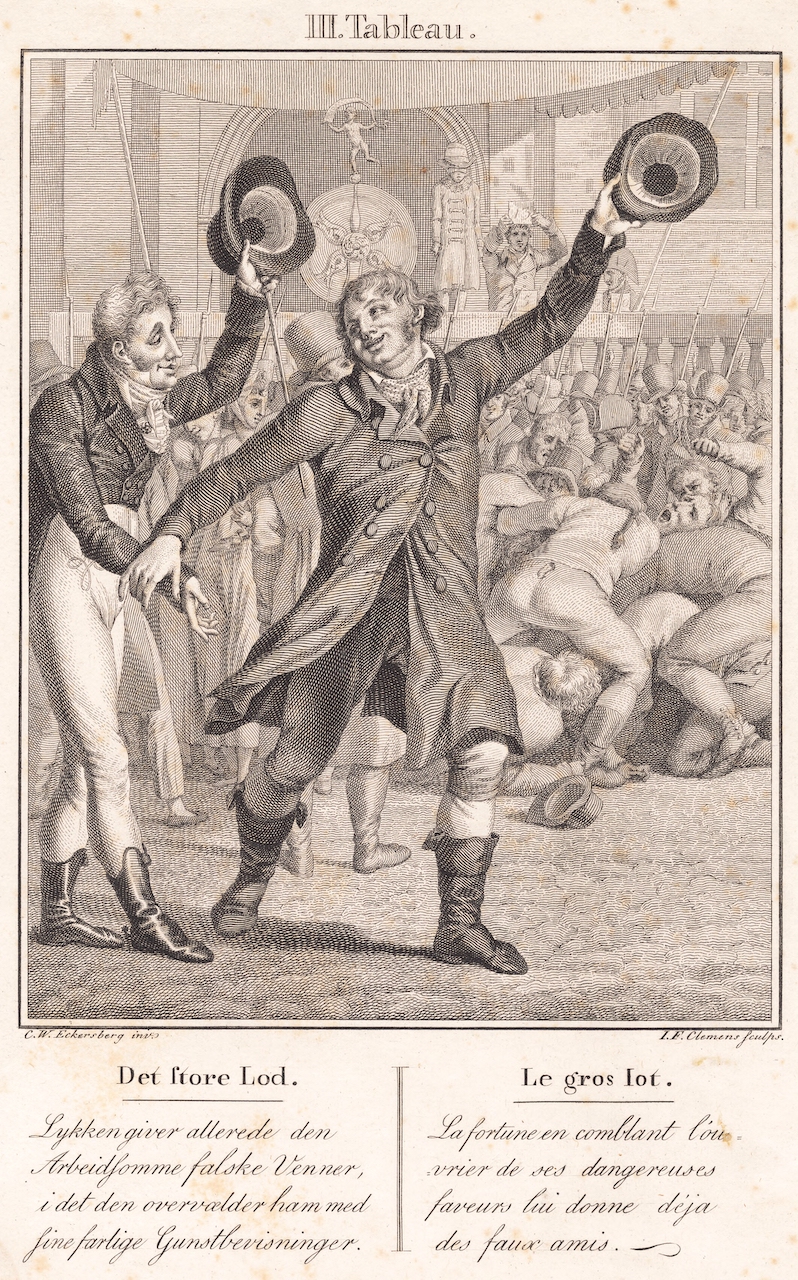

The lotto quickly became wildly popular; in principle, “everyone” wanted to, and could, participate, as the entry fee was so low, and the number of tickets was unlimited. However, this ‘lotto mania’ did not go unnoticed by critics. Thanks to the contemporary press freedom, several enlightened patriots grasped their pens in the hope of leading the king’s subjects back on the straight and narrow path. The debate on the ‘hazardous lotto’ was the longest lasting in the press freedom era and is represented in the civil servant Bolle Willum Luxdorph’s (1716–1788) collection of “press freedom writings”. The lottery debate is discussed by Henrik Horstbull, Ulrik Langen and Frederik Stjernfeldt in Grov konfækt. Tre vilde år med trykkefrihed 1770–73 (2020), as well as in Ulrik Langen’s article “«The Worst Invention Ever»: The Number Lottery and Its Critics During the Press Freedom Period in Denmark-Norway 1770–1773” (2023).

The debate went on throughout the entire press freedom era, i.e. 1770–1773, and presented a series of warnings against the new and alluring game. Readers were warned about how this lottery threatened not only to ruin the poor, but also to destruct every single European state – including Denmark-Norway . One of the reasons for such warnings was the immense popularity of the lottery. The number lottery was marketed in such a way that it appeared easy to win, while in reality it was quite the opposite.

Several of the pamphlets in the debate took the form of didactic explanations – or in other words, attempts to educate the general public about how fraudulent the number lottery really was. To explain how low the probability of winning was, the lottery debaters sought explanations via easily understandable equations; the winning numbers were for example compared to everything from windows in the streets of Copenhagen to digging for treasures along the paths of Sjælland. Nevertheless, popular notions of Lady Fortuna and her wheel of fortune, not to mention the popular belief in predicting or reading ‘lucky numbers’ in both coffee grounds and cloud formations, still seemed to strengthen the lottery dreams and fantasies of the commoners.

Alongside the lottery debate, the Luxdorph collection also contains a number of fictional texts dealing with the lottery. Here, we find humorous skillings ballads, such as ‘En lystig Lotterie-Viise’ (unknown date, probably 1773), but also parodies of the so-called ‘dream manuals’ that flourished on the market.

In light of the ongoing lottery debate, these humorous texts can also be read as didactic: by laughing at how stupidly lottery players behave, the commoners might perhaps learn to leave the lottery altogether. More interesting in this context, however, are the glimpses of popular belief that also shine through the fictional texts. In the fictional, humorous and satirical texts in the Luxdorph collection, there are references to both Lady Fortuna, the wheel of fortune, and ‘true’ dream manuals – built on the idea of literally being able to ‘dream oneself rich’ – a recurrent trope even in other skilling ballads from this period. The idea of predestined lottery draws was thus represented in fictional literature.

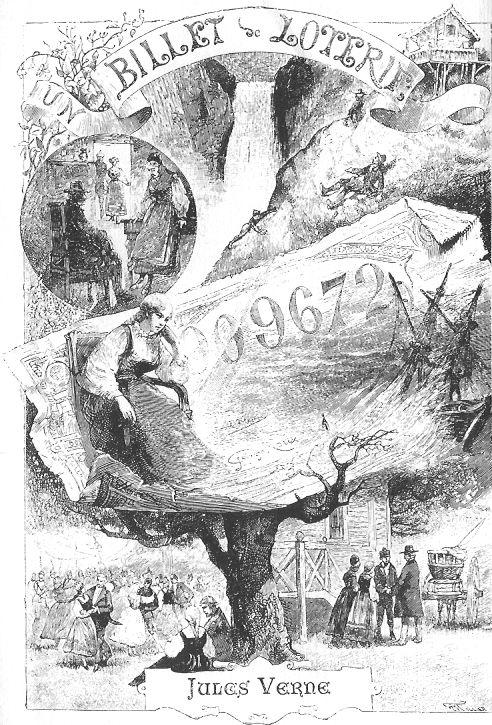

Now, let’s head a hundred years forth, to the late 1800s, and popular ‘lottery literature’ presented in this period. What kind of picture do we get? In what follows, we shall look at two examples: 1) Jules Verne’s novel Un Billet de Loterie, le Numéro 9672 (1886) and 2) Martin Andersen Nexø’s novel Lotterisvensken (1896). Although, at the time of publication of these two books, most people knew that lottery draws are determined purely by chance, the two novels tell completely different stories. In fiction, as we shall see, fate still prevails.

The scene in Jules Verne’s novel Un Billet de Loterie is set in Norway. Here we meet the young sweethearts, Hulda and Ole, who have recently become engaged. In order to raise enough money to get married, Ole travels abroad on a fishing boat. However, the boat encounters a terrible storm and Ole fears for his life. In desperation, he sends a message in a bottle to Hulda. In the bottle he also leaves a lottery ticket with four numbers that he is convinced will be drawn. Luckily, the bottle is found by an honest soul, who ensures that Hulda receives the ticket – and, surprise, surprise: the numbers are finally drawn, leaving Hulda with a great price. As if this weren’t enough, in the end it turns out that Ole also miraculously survived the shipwreck, allowing the story to have a double happy ending – all in line with the rules of comedy.

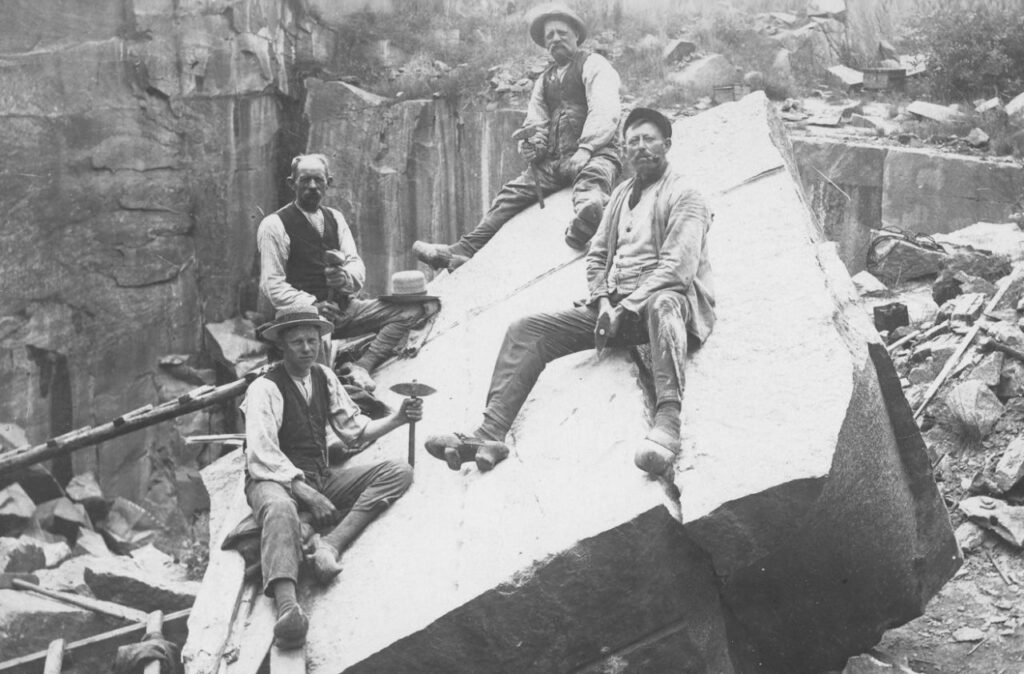

Things don’t go quite as well in Martin Andersen Nexø’s novel Lotterisvensken. Here, the scene is set among poor quarry workers on the island of Bornholm, Denmark. The book’s protagonist, which is also the title figure, has emigrated from Sweden and daily risks both life and limbs to provide for his family.

In the opening scene of Nexø’s novel, we meet the Swede on his way to a lottery collector. The Swede has decided to try his luck in the lottery. The ticket turns out to be more expensive than he expected, and soon foreshadows the manyfold defeats he will face. Hoping to impact his chances of winning, the Swede tries different tactics. As the draw approaches, he even softens like a lamb; surely, he prays, God must recognise this and give him a hand when the numbers are to be drawn. But God doesn’t listen to his prayers. In the drawing, the neighbouring numbers are drawn, like an irony of fate.

This experience of almost winning leads the Swede into a vicious circle; he gambles beyond means, and the losses becomes more and more painful. In the end, he ends up gambling away his lottery ticket, in a so-called ‘stick game’ at the local pub. Thereafter it goes as it must when the literary laws of tragedy govern the draw: the numbers of his lost ticket are drawn, providing a great prize to its new owner. When the Swede finally wins, in other words, he has already lost everything – after which he leaves the scene, taking his own life in the quarry.

We know that, as humans, we tend to believe in stories with recognisable plot structures. This idea underlies historian Hayden White’s theory of history and narrative in Metahistory (1973), where, in short, he equates the (unconscious) choice of historians to construct history in narratives with the persuasive power of literary structures. When a (hi)story is recognised as a comedy or a tragedy, the readers are more likely to perceive it as being ‘true’.

In conclusion, we might ask whether this can also be the case with lottery stories? Could fictional representations of lottery drawings with happy or tragic endings have influenced the way we think about putting money into the lottery? It is certainly not inconceivable that it could lead at least some of us to stick to our series of ‘lucky numbers’, and not least: To always renew the ticket – so that the prize doesn’t slip away the one time we didn’t.

Inga Henriette Undheim

Inga Henriette Undheim is Associate Professor at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. She is an expert in eighteenth-century Dano-Norwegian literature and has also published articles on Norwegian nineteenth-century literature. Her main contribution to the project will be to explore the lottery fantasy in the Scandinavian periodical press and fiction, including children’s literature, as well as providing comparative perspectives on eighteenth-century and contemporary versions of the lottery fantasy in different literary genres.