By Michael Scham

A major argument in favor of introducing the lottery in Spain (1763) was that it represented a solution to the perennial problem of gambling. From the Middle Ages on, an abundance of tractates, legal documents, moralistic writings and literary works expressed a preoccupation with rampant gambling, in diverse venues, at every level of society, and through an astonishing variety of games. Even relatively progressive thinkers who promoted the value of leisure and play were wary of the financial and moral peril of gambling—particularly with games of chance. This would seem an unpropitious backdrop for proposing a State Lottery. And yet, as with other seemingly ineradicable “vices,” such as prostitution or drug use, the idea was that legalization allowed for curtailing damaging excesses through regulation and, not least, for channeling profits to worthy causes.

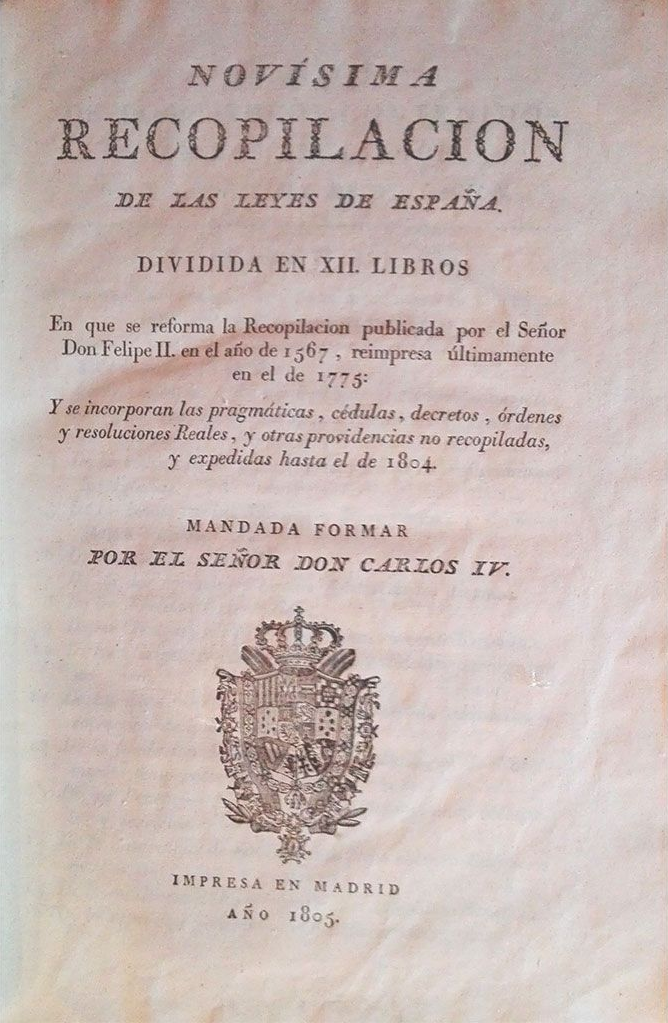

The Spanish lottery, in its various iterations, enjoyed an uninterrupted existence, and is highly visible in Spain today. This longevity is not necessarily a result of having achieved its goal of curtailing illicit gambling. For a window into the state of gambling in the years following the introduction of the lottery in Spain, we can look to the Spanish law code of 1805, the “Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España.” A series of promulgations by Carlos III, the enlightened monarch who introduced the lottery, would suggest the effects were inimical to those anticipated.

Title 23 (Vol. IV, Bk. XII), on prohibited games (“De los juegos prohibidos”), contains laws from the fourteenth century onwards dealing with cards, dice and gaming houses. The first entry from Carlos III is in 1764, the year following the commencement of the Spanish lottery. Here we find the monarch attempting to support the public order campaign by not only reaffirming previous prohibitions against betting and games of chance (“juegos de envite, suerte y azar”), but also by voiding privileges for playing that had been given to certain estates (“Derogacion de todo fuero privilegiado”). By 1771, the year of the introduction of the lottery in the colonies (“Nueva España”), the exasperation is palpable: “Habiendo sabido con mucho desagrado, que en la Corte y demas pueblos del reyno se han introducido y continuan varios juegos…” Ley XV). The king expresses chagrin at learning of the continued playing of prohibited games, as well as the introduction of new ones. He also attempts to limit the amount one can wager on licit games (those of skill rather than chance), and prohibits betting on credit or with items of value (jewels, garments, furniture). Additionally, he stipulates temporal boundaries on playing, and places a ban on most games (licit or illicit) in particular venues, such as taverns, inns, cafés, and other public houses. In 1786—twenty-three years after the introduction of the lottery in Spain—Carlos again feels the need to re-assert and promulgate the laws of 1771, many of which were in themselves reminders of previous ordinances (“Observancia de la anterior pragmática prohibitiva de juegos de envite, suerte y azar” Ley XVI).

In addition to having apparently null effect on gambling across all sectors of society, the introduction of the lottery in Spain seemed to create new problems specific to this state-sanctioned game: the king is compelled to reassert the prohibition of foreign lotteries in 1774 (Ley XVIII), and, to top it all off, must then contend with unsanctioned raffles based on the lottery drawing (“rifas á los extractos de la lotería” Title XXIV 1787)—an innovative form of subsidiary gambling. Given this Scylla of regenerating heads, the answer to our initial question seems to be a resounding “no”: not only did the lottery’s introduction fail to curtail illicit gambling; it actually served as an impetus for the invention of new transgressions. Although anti-lottery polemicists of various stripes—religious traditionalist to progressive, Enlightenment thinkers—were thus vindicated, the lottery itself survived and prospered. After all, a new and dependable revenue stream had been established, and a financially strained Crown wary of imposing new taxes was unwilling to do without it.

Michael Scham

Michael Scham is Associate Professor of Spanish at NTNU. He is a specialist in early-modern Spanish literature and is the author of “Lector Ludens”: The Representation of Games and Play in Cervantes.