By Marius Warholm Haugen

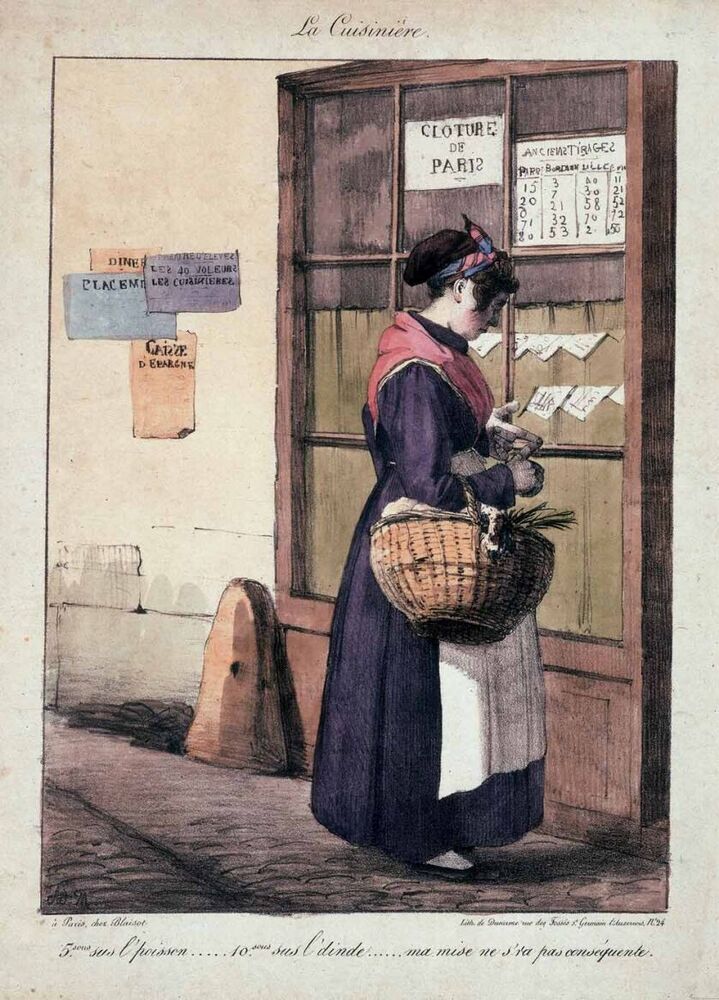

In the French context, the nineteenth-century collective imagination seemed to have developed a typology of different lottery players, of which one recurring type was “la cuisinière”, the cook, reputed for skimming off from her employer’s food budget to pay for the stake. This is the subject for Emmanuel Adolphe Midy’s drawing “La Cuisinière”, which can be found in the collection of the Belgian Lottery Museum.[1]

The drawing depicts a cook standing in front of a lottery office, holding a grocery basket, while counting on her fingers. The legend reads: “5sous sus l’poisson… 10sous sus l’dinde… ma mise ne s’ra pas conséquente” [5 sous on the fish… 10 sous on the turkey… my stake will not be of consequence” All translations into English are my own.]. We see her trying to figure out how much she can take off her grocery expenses without being caught stealing.

A poster to the left seemingly advertising for a “Caisse d’Épargne”, a savings bank, provides a significant historical and sociological marker here. Established in 1818 by liberal, philanthropic bankers, who sought to procure the modest classes with a way to escape poverty, the institution of the savings bank was presented as the antithesis of the lottery, as a more secure investment of one’s savings. This new institution lacked, however, the seductive power of the lottery, with its promise of sudden, exuberant wealth.

This difference in lustre is the topic of Mazères and Romieu’s 1823 vaudeville-comedy Le Bureau de loterie [The Lottery Office], in which the cook Joséphine scorns the savings bank and dreams of nothing but winning the lottery: « Chut. Parlez-moi de la loterie.. ! Voilà une bonne chose.. ! Au lieu que votre caisse d’épargne… »[2] [Hush. Talk to me about the lottery! There is a good thing! Whereas your savings bank…] Joséphine also steals from her employer, in order to “nourish” four numbers:

Joséphine: “Vous savez bien que depuis long-temps je nourris quatre numéros.[3]”

Loquet : “Oui… ; et pour les nourrir vous prenez sur le dîner de vos maîtres… vous enflez le mémoire… et les quaternes passent sur le beurre et les légumes”.

[Joséphine : “You know that I have for a long time been nourishing four numbers.”

Loquet: “Yes…; and to nourish them you take from the dinner of your masters… you inflate the budget… and the quaterne [the four numbers] go from the butter and the vegetables.”]

The expression “nourrir des numéros”, to nourish the numbers, had become a common expression in the era of the French national lottery, to describe the practice of repeatedly playing a set of favourite numbers. In this comedy, the expression joins with the commonplace of the thieving cook to form the pun of Joséphine’s interlocutor.

The character of the cook appears not only on stage and in visual form, but also in prose fiction, as a representative of the modest classes playing the lottery and dreaming of a better life. She is, more often than not, depicted with sympathy and humour, despite her tendency to take money from her employers to play. In a short story written by the prolific feuilletoniste Frédéric Soulié, “La Nièce de Vaugelas” [Vaugelas’s niece], the narrator’s cook also represents the modest aspirations of the common people, whose dreams are restricted by their own social horizon. The short story references the abolition of the French Loterie Royale, killing the dreams and illusions of the players:

Car ils nous l’ont tuée, notre loterie ; ils nous l’ont tuée à nous tous, à moi, à vous, à lui, et à ma cuisinière aussi, à Rosalie, qui ne rêve ni châteaux, ni parcs, ni équipages, mais qui rêve qu’elle aura une cuisinière et que cette cuisinière ne volera pas. Nobles illusions, je vous dis adieu pour elle et pour moi ![4]

[For they killed it, our lottery; they killed it for of all of us, for me, for you, for him, and for my cook also, for Rosalie, who dreams neither of palaces, nor parks, nor carriages, but who dreams of having a cook and that this cook will not steal. Noble illusions, I bid you farewell from her and from me!]

Not only is Rosalie dreaming primarily of having someone else cook for her, but she also, somewhat ironically perhaps, hopes that her cook doesn’t steal.

A final example of an author taking an interest in the commonplace of the lottery-playing cook is the great sociological observer, Honoré de Balzac. He references the figure in two novels, in both cases discussing the effect of the abolition of the lottery, and its relationship to the savings bank. The first occurrence is in the 1837 novel La Maison Nucingen [The Firm of Nucingen], in which the character Blondet deplores an abolition that has not solved the problem of domestic theft, only aggravated it: “Vous supprimez stupidement la Loterie, les cuisinières n’en volent pas moins leurs maîtres, elles portent leurs vols à une Caisse d’Épargne, et la mise est pour elles de deux cent cinquante francs au lieu d’être de quarante sous” [You stupidly abolish the Lottery, the cooks do no less steal from their masters, they carry their thefts to the Savings Bank, and the stake is for them at a hundred and fifty francs instead of forty sous][5]. Balzac develops the image and the argument further in the novel La Cousine Bette (1846-1847):

Dans tous les ménages, la plaie des domestiques est aujourd’hui la plus vive de toutes les plaies financières. […] Là où ces femmes [les cuisinières] cherchaient autrefois quarante sous pour leur mise à la loterie, elles prennent aujourd’hui cinquante francs pour la caisse d’épargne. Et les froids puritains qui s’amusent à faire en France des expériences philanthropiques, croient avoir moralisé le peuple ![6]

[In every household, the plague of servants is today the most lively of all financial plagues […] Where these women [the cooks] used to look for forty sous for their stake at the lottery, they take today fifty francs for the savings bank. And the cold puritans who amuse themselves by doing philanthropic experiments in France, they believe that they have moralised the people!]

The figure of the cook, as we see her in Midy’s drawing, on stage, or in prose fiction, thus appears both as intimately linked to the historical phenomenon of the lottery and stretching beyond it, always seeking somewhere or something in which to invest her dreams of a different life. All these examples attest, nonetheless, to the cook being, in the early nineteenth century, an emblematic figure for the lottery, a representative for the modest player.

[1] See https://www.museedelaloterie.be/collection/la-cuisinière.

[2] Edouard-Joseph-Ennemond Mazères and Auguste Romieu, Le Bureau de loterie, comédie-vaudeville en un acte (Paris: J.-N. Barba, Libraire, 1823), scene V, p. 10.

[3] Le Bureau de loterie, scene V, p. 11–12.

[4] Frédéric Soulié, “La Nièce de Vaugelas”, in Un été à Meudon (Brussels: J.P. Meline, 1836), p. 16.

[5] Honoré de Balzac, La Maison Nucingen (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1989), p. 191.

[6] Honoré de Balzac, La Cousine Bette (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2019), pp. 234–35.

Marius Warholm Haugen

Marius Warholm Haugen is Professor of French Literature at NTNU. Specializing in eighteenth-century studies, he is particularly interested in transnational exchanges, circulation, and translation in and between Italian, French, and British literature. He will conduct research on the representation of the lottery fantasy in French print culture and its connections to Italy and Britain.