By Angela Fabris (Klagenfurt)

When scrolling through some texts published in Venice around the middle of the eighteenth century that deal with the lotto, it is possible to discover a certain ambivalence in the judgment reserved for it; and this is with regard to the choice of numbers, the positive or negative effects resulting from them and, of course, also to the profile of the masculine and feminine player involved. The variety and fluctuating nature of judgments is found not only in texts from different authors but, and this is significant, even in different writings by the same author.

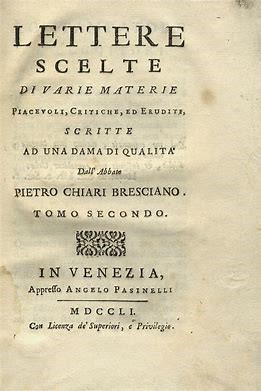

This is the case, for example, with Abbot Pietro Chiari, author of the La giuocatrice di lotto (1757), on which Marius Warholm Haugen wrote a fine essay[1], who touches directly on the lotto also in a book of letters entitled Lettere scelte di varie materie piacevoli, critiche ed erudite scritte ad una dama di qualità dall’Abate Pietro Chiari bresciano (Selected Letters of Various Pleasant, Critical and Erudite Matters Written to a Lady of Quality by the Brescian Abbot Pietro Chiari).

The letter in question is found in the first tome of 1752 (published by Angelo Pasinelli in Venice) on pages 122-128. In the opening, the abbot points out how his accompanying fame – that is, his being considered wise as a traveler – had prompted his interlocutor’s cousin to consider him an oracle, begging him to send her five numbers to play at the public “Lotto” (p. 123). He therefore disposes himself to study the matter, of which he offers an interesting account a few days later, specifying how they are to be pitied by certain “men of a palm” (“Uomiccioli d’un palmo”) and certain “Donnicciule of half a pound” (“Donnicciule di mezza libbra”) who think that wonderful virtue is concealed in the numbers of the Abacus. He also emphasizes how each number has its advocates. This is the case with the one and three as symbols of the trinity, seven in accordance with the wonders of the world or, for example, the number 10 which “in itself contains even, odd, cubic, long, wide, and square numbers” (“in sé contiene de’ numeri pari, dispari, cubici, lunghi, larghi, e quadrati”).

The system proposed by Abbot Chiari is thus to favor the numbers which everyone feels they have the greatest devotion to. Whether or not those same numbers will then come out in the next draw depends solely on “Chance” (“Caso”) since, and here the parodic intention is evident, each of the numbers contained in the urn has an equal chance of being drawn.

He goes on to criticize the divinatory abilities of dreams, which he deems totally fallacious to the point of describing them as the great force of popular ignorance (“many think they can discover in sleep the secrets they cannot discover while awake”; “molti pensano di poter scoprire dormendo i segreti che non possono scoprire da svegli”). Therefore, he concludes, there is no point in studying possible lotto combinations. On the contrary, he adds, every man of sense must play the lotto according to his own strength; and, in this sense, he points out the lack of lucidity (“salt in the noggin”; “sale in zucca”) of those who gamble everything down to their shirts, by simply relying on a dream, puerile observation, or superficial conjecture.

In this letter, it is therefore possible to observe how Chiari advocates a certain caution toward the game of lotto and how he destroys the popular belief that it is possible to predict the winning numbers.

Another paradigmatic case is that of Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793; fig. 2), who bears tendentially critical attitudes towards the lotto in his comedies. Something partially different happens, however, in the three-act prose comedy Le donne gelose (in Venetian dialect), which was first successfully performed in Venice in the Carnival of 1752.

At the center of the story is the widow Lugrezia, the protagonist, along with the male characters who rely on her for directions or suggestions on numbers to play in the lotto. In general, the gamblers’ hopes of winning are not linked with ideas of sudden enrichment and ambitions for social mobility, but rather a desire to restore an economic situation affected by bad business, gambling losses or, on the part of the protagonist, the aspiration for a modest economic improvement according to a proto-bourgeois perspective.

The earliest information concerning Lugrezia, in the female chatter anticipating her appearance on stage, in fact emphasizes her assiduous participation in theatrical premieres and having an abundance of clothes thanks to the earnings from the lotto.[2] This initial portrayal is contrasted, on the other hand, by the skepticism of another female interlocutor, who considers it unlikely that Lugrezia’s wealth could come from her lotto winnings (“Ghe vol altro che lotto!”),[3] reflecting a series of swinging judgments around the practice of playing the numbers.

After this initial connection between the protagonist and the lotto, this situation recurs in the dialogue that takes place in Lugrezia’s home in the sixth scene of Act I, with the discussion around the numbers to be played. Here we do not witness any parodic or satirical twist on the strategies used to play the numbers like what happens – according to what Marius Warholm Haugen timely notes in his essay –[4] in La donna di garbo.

In fact, Boldo trusts in the predictive abilities of the widow who, in turn, relies on the interpretation of dreams to decide which numbers to play, reasoning about possible attributions. In this sense, the figure of Lugrezia proves to be particularly interesting in becoming the promoter of a form of independence sustained by her skills in social relations unlike other male Goldonian characters for whom, as rightly pointed out by Antonella Rigamonti and Laura Favero Carraro, gambling becomes an obsession that affects social interaction.[5]

In the meantime, the woman’s predictions come true; Boldo returns announcing the victorious release of the “terno” (fig. 3) with a prize of 1,800 ducats, reflecting Goldoni’s positive attitude toward the lotto. The win makes it possible to restore a family’s peace that otherwise would have been permanently destroyed due to some economic difficulties. This is accompanied by the enthusiasm of Harlequin who, in scene XII of Act III, as he is carrying drinks and food for the celebration, bursts into a meaningful “viva el lotto”.

Even in this case, however, there is no lack of caution. In the last scene, in fact, Lugrezia recommends to Boldo to abandon the lotto, reflecting a moderately positive but rational attitude toward the numbers game. We also witness the protagonist’s satisfaction with the independence she enjoys, the same independence that Boldo’s wife desires, who, after her husband’s lotto winnings, would not mind being a widow; where we observe an openness to a form of female self-determination fostered by lotto winnings.

[1] Marius Warholm Haugen, The Lottery Fantasy and Social Mobility in Eighteenth-Century Venetian Literature: Carlo Goldoni, Pietro Chiari, and Giacomo Casanova, in Italian Studies, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2022.2069409.

[2] Carlo Goldoni, Le donne gelose. Commedia di tre atti in prosa. Rappresentata per la prima volta in Venezia nel Carnovale dell’anno 1752, Venezia, 1910, tomo VIII, p. 115 consultabile in Opere complete; : Goldoni, Carlo, 1707-1793 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive (12.1.2023).

[3] Ivi, p. 115.

[4] Marius Warholm Haugen, The Lottery Fantasy and Social Mobility in Eighteenth-Century Venetian Literature: Carlo Goldoni, Pietro Chiari, and Giacomo Casanova, in Italian Studies, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2022.2069409.

[5] See A. Rigamento e L. Favero Carraro, Woman at stake: The Self-Assertive Potential of Gambling in Susanna Centlivre’s The Basset Table, in Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Theatre Research, 16 (2001), 53–62: 54.

Angela Fabris

Angela Fabris is an Associate Professor of Romance literature at the University of Klagenfurt and a visiting professor at University Ca’ Foscari Venice. Her research touches different themes, figures, and times in Italian, Spanish, French, and European literature, also from a comparative perspective, from Boccaccio to the Baroque novel of the Siglo de Oro up to the genre of the “Spectators” and the journalistic production of Gasparo Gozzi (I giornali veneziani di Gasparo Gozzi.Tra dialogo e consenso sulla scia delloSpectator, Biblioteca di «Lettere italiane», Studi e testi, vol. 79, Olschki, 2022). She participates in an international research project on Pregoldonian theater (https://www.usc.gal/goldoni) and is one of the leaders of The Invention of the Lottery Fantasy – A Cultural, Transnational, and Transmedial History of European Lotteries, funded by the Research Council of Norway (https://www.ntnu.edu/lottery). She has written several essays on the film genres of science fiction, horror, and eroticism. She directs the AAIM series in volume and open access with the publisher De Gruyter (Alpe Adria e dintorni, itinerari mediterranei (degruyter.com) and research about Mediterranean literature and film, to which she has devoted a series of essays concerning the treatment of space.